The boy was looking at me like I was crazy. I can still see his face, bemused and laced with disdain.

“Why are you answering? You’re a girl!” It was a primary school assembly and the teacher had just asked a question, specifically directed at the boys, to which I had responded effusively. The boy’s words doused me like a bucket of icy water.

“Oh yes,” I remembered with a start, “I’m a girl.”

That was the first time I realised that despite being female, I’d assumed I was male. And it was not to be the last.

Most children, or so I’ve gathered, know what sex they are, but I required regular reminders. It's not that I longed to be a boy, or told people, “I'm a boy,” I just assumed I was. And I can’t remember a time before it.

From the earliest age, girls seemed foreign to me. I wanted to play games like ‘Escape from the Stampede’ (heavily inspired by The Lion King, not gonna lie), but the girls were not interested. In fact, they didn’t seem to want to play games at all. They just wanted to talk - a more boring use of my time I could not possibly imagine! The boys didn’t want to talk; they wanted to play games, pretend to fight bad guys and run up and down the hill… just like me. It was as though the girls spoke a different language, but the boys spoke a language I understood. It was easy to assume I was one of them. However, reality would often bite back. Feeling, as I did, this kinship with the boys, I would attempt to join in their football games, but they would reject me outright for being a girl. When assailed by the truth of my sex, I never insisted that I was a boy - the physiological evidence to the contrary was undeniable, even to a five-year-old.

So, there I was in no-man’s-land. Isolated from the girls and not accepted by the boys, I played on my own. I never blamed the boys. I knew they were right - I was indeed a girl. I didn’t have a leg to stand on. As for the girls, I’m afraid I was less charitable. I suppose I blamed them for the annoying female norms that thrust themselves upon me in my everyday life. For example, when toys were handed out, I would get given the Barbie, my brother, the Action Man. This exasperated me no end. What does Barbie even do? She stands around with a hairbrush and a mirror. Meanwhile, Action Man is abseiling, hang-gliding and launching missiles. It was obvious to me which toy was the superior, but incredibly, a lot of the girls seemed to prefer Barbie! The recognition of such a pattern, over time, bred in me a kind of contempt for girls and women. I judged them to be vacuous, vain and dull. When something would come along to remind me I was female, I would always feel deflated - as though I’d been rudely awoken from a wonderful dream. As I got older, I strove to disassociate myself from anything that was considered feminine.

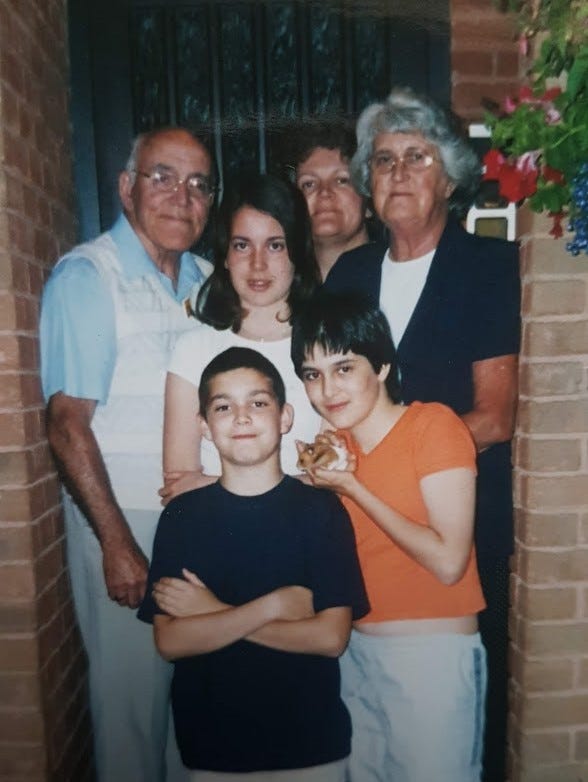

As soon as I was old enough to choose my clothes, I refused point blank to wear skirts or dresses. I remember my poor mum pleading with me to wear something nice for my grandparents’ big anniversary party. She did not win. The grainy old home video shows a black tie event with a teenage girl in blue Adidas jogging bottoms. As a teenager, I paid zero attention to my physical appearance. Despite my mother’s entreaties, I refused to wash or brush my hair. I did not care that it was a matted, knotty mess. Eventually, when it had reached the status of legitimate health hazard, she gave me an ultimatum. Wash your hair or I will cut it all off. I didn’t think she’d follow through on her threat. She did.

My masculine appearance contributed to several instances during my teenage years where I was mistaken for a boy. Most embarrassingly, our deputy headmaster once called upon me in front of the entire class to run an errand, addressing me as ‘young man’ - to much harsh laughter from the boys.

It is a strange thing, when I consider it, that as a child I should at once have felt pain upon being reminded I was female and shame upon being taken as male. What was wrong with me? I carried a sense, deep down, that I was defective.

I completed sixth form college and went on to study Media at the University of Sussex in Brighton. Around this time, I started noticing the fact that my body had changed (better 5 years late than never!) When trying on clothes, my body was a constant reminder of my femaleness, so I relaxed my rigid dress code and allowed some skirts and dresses into my wardrobe. Nevertheless, my default perception of myself changed little. I drifted through life thinking that I was male and, what’s more, that other people saw me as male. During the times where I was aware of my ‘femaleness,’ envy would often flare up within. I would dwell - sometimes with bitterness - on how much better my life would be were I a man. In short, I flitted between thinking I was a man and wanting to be one. The medical label for this condition is gender dysphoria, which is defined as ‘The persistent distress and discomfort with one’s biological sex.’

While this was indeed the case, I do not wish to portray my life as miserable. Overall, I was very happy. After all, there are not too many instances in daily life where one’s sex comes into play, and even when it did, I was used to the feelings such incidents brought up. After university, I got a job working for my church as a video editor and there I stayed for several years. During this time my sense of dysphoria worsened as I was surrounded by lots of really sweet, pastorally-gifted women. I have always had very low levels of empathy so their presence (however unwittingly) was a constant reminder of how far I fell short. I couldn’t help but feel like a failure as a woman when someone was grieving in front of me, the other women were visibly moved, but I felt nothing. Life continued.

At 25, I cut all my hair off, only this time (apparently) it was chic! Pixie cuts were all the rage. My colleagues at work cooed over me and said that some lipstick would complement my new look. So at lunchtime they took me down to Boots and bought me some red lippie. I was not used to wearing makeup and as they applied it, I felt like a clown. I distinctly remember walking home from work that day with a strong sense of shame. My eyes darted around, paranoid. When walking past strangers, I expected them to stop and stare at me, as I felt like a man in drag. Then I remembered I was not in fact a man and what they saw when they looked at me was a woman wearing lipstick, which, after all, was not out of the ordinary. Twenty years had passed since that first incident in school assembly, yet still I was experiencing those pin pricks reminders that I was not the sex I thought I was.

Around the same time, following a build-up of problems in other areas of my life, I sought an autism diagnosis. I’d suspected for a long time that I was on the spectrum. Looking back, I didn’t actually understand autism amazingly well, but I knew enough about it to recognise several of its key symptoms. After an uncharacteristically short time on the NHS waiting list, I received a formal diagnosis for Autism Spectrum Disorder. The clinician who diagnosed me described me as ‘an open and shut case of an adult female with autism.’

As I looked into my new condition, I discovered more about how autism affects the brain. There isn’t time enough to go into the neurology here, but very long story short, it is clear from the scientific literature that the autistic brain resembles an exaggerated version of the typical male brain. I am not referring to stereotypes here, but to the scientifically proven cognitive distinctions that characterise the way most men think. To most people, the fact that men and women think differently (in general) is self-evident, but if you are interested in the studies that show it, I would highly recommend ‘The Essential Difference’ by Professor Simon Baron-Cohen. Anyway, as I was saying, the autistic brain could be described as hyper-masculine. Learning this changed everything for me. It became clear to me why I had related so much to the boys, while the girls had seemed so alien. It became clear to me why I was less empathetic than the other women in my life. And the answer was not that I was male. Nor was I defective. I was autistic. I was not outside the category of female, I was just a rarer type of female. This realisation allowed me, gradually, to see myself as female. Essentially, I let myself into the club from which I’d always rejected myself, and at which I had always looked with derision.

The acceptance of myself as female did not happen overnight. Rather, it unfolded slowly over a matter of years. In fact, it was several years after my diagnosis of autism that I dared even to tell anyone about my struggle with gender dysphoria. In the end, it was my dear friend Ruth in whom I confided. Perhaps ‘confided’ is not the most accurate word. In fact, I bawled my eyes out to her for several hours in a stairwell. Good times. This first moment of honesty opened the door to many years of therapeutic conversations with pastors, friends and fellow Christians. At every step, I was met with compassion and a listening ear. But true love sometimes hurts. On one occasion, I was complaining to my pastor, Stephen, that women were boring and vain. To my surprise, he pointed out that I was being sexist and advised me to repent. He was right. The vision of ‘woman’ that I had been holding in my mind was an amalgamation of the worst excesses of the most vapid and mindless women I had come across in my life. I had conflated all women with ‘her’, somehow managing to dismiss the myriad women I’d met who did not fit that mould - women who were funny, sharp and principled. I repented immediately.

This propensity to look at a complex set of data and come to overly simplistic conclusions is a well-known facet of the autistic mind. Autistic people are notorious for their aversion to change and instability. We need to know exactly where we are in order to feel safe. Nuance and subtlety, therefore, are the autistic person’s natural enemies. I believe this black and white style of thinking was another contributing factor to my gender dysphoria. When I noticed, at a young age, that I differed from my female peers, I could not deal with the complexity of a sliding scale of personality types ranging from feminine to masculine. Instead, I saw only two categories: girls and boys. Subconsciously, I thought: ‘I clearly do not fit in with the girls. Therefore, I must be a boy.’

I was diagnosed with autism in 2015, and for the last 4 or 5 years, I can honestly say I have not found myself thinking I am a man. I am at home with the fact I am a woman. More than that, I am happy being a different kind of woman. Many of the autistic character traits of which I was once ashamed I now see as strengths. I’ve never been happier. That’s not to say that I don’t sometimes get frustrated by the hurdles that come with womanhood, but I have accepted that being a sex - either sex - comes with challenges. There are many expectations and burdens placed upon men with which I will never have to contend. I try to be mindful of that on the odd occasion when I find myself lamenting that the grass is greener on the other side of the fence. But at least now I know which side of the fence I am on! What’s more, I find myself gazing over that fence less and less often.

Yes, things are much better for me now, yet, as I look at the current narrative about gender, I am deeply concerned. The number of girls identifying as transgender (and seeking medical intervention as a result) has absolutely skyrocketed over the last few years - and studies have shown that a huge proportion of these girls are autistic. I worry for them. It took me a long time to process who I was and introduce some nuance into my rigid convictions about the world. How much harder must it be for modern teenagers who are constantly being told that whether they are a boy or a girl is dictated by their feelings rather than their physiology? I wrestled with my identity, but I always knew this to be true:

“You are a girl whose mind causes a disconnection from that reality.”

Never was I told the lie that girls are now being told:

“You are a boy whose body causes a disconnection from that reality.”

I am so grateful to God that I was shielded from this poisonous idea. It meant that in seeking a solution to my problem, I knew my mind had to be brought into alignment with my body. I was not charmed by the horrific solution offered by today’s activists: ‘Bring your body into alignment with your mind… even if it means getting a hysterectomy.’ I shudder to think that, had this ideology been around when I was a teenager, I would probably be sitting here right now with an irreversibly mutilated body and a whole reservoir of regret.

It is worth my noting at this point that gender dysphoria is not always caused by autism. It can be felt by anyone who does not naturally conform to conventional gender stereotypes. Other factors such as the disturbing onset of puberty, the terrifying expectations thrust upon them by pornography, as well as various mental health issues, can cause adolescent girls in particular to see the rejection of their sex as a means of escape.

But autism is my story. The very first time that I sat down to discuss my dysphoria with Stephen and his wife, after several hours of weeping had passed and the shame was still raw, I said to them, “I have a feeling that sometime in the future God is going to use my story to help other people.” I believe that, by the grace of God, that time is now. I am determined to speak out so that anyone who feels like they don’t fit in, anyone who feels like a failure, and anyone who doesn’t know just how valuable they truly are can hear at least one voice telling them, as cliched as it may sound, “You are beautiful just the way you are.”

Just watched your triggernometry episode… I have never heard anyone else with a story so like my own who is also a Christian. I’ve had the same comment made to me by a pastor that I’m great to have around in a crisis cos I think so clearly and unemotionally.

Thank you for sharing, Jojo

Thank you so much for speaking out about this! I am autistic and can relate a lot to your experiences in that I have never felt that I fit in much with women because of my lack of empathy and analytical mind. In grade three, I began asking people to call me by a boy's name, but thankfully, none of the adults in my life did. I truly think that if my parents did not raise me to have a strong Christian faith, I would have transitioned and ended up regretting it.